BCAAs: Wasting Money? An Evidence-Based Look for US Athletes

Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) are popular supplements among US athletes, yet extensive research suggests that for most individuals consuming adequate protein, BCAA supplementation offers no additional benefits for muscle protein synthesis, recovery, or performance, potentially rendering the investment redundant.

For US athletes constantly seeking an edge, the world of supplements can be a dizzying array of promises and claims. Among the most pervasive are branched-chain amino acids, or BCAAs, heralded by many as essential for muscle growth and recovery. But with a closer look into current scientific literature, it’s worth asking: BCAAs: Are You Wasting Your Money? An Evidence-Based Analysis for US Athletes.

Understanding BCAAs: What Are They and Why the Hype?

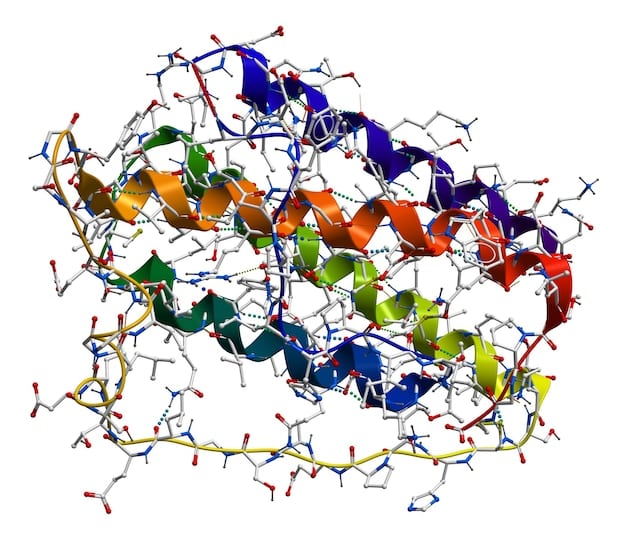

Branched-chain amino acids—leucine, isoleucine, and valine—are essential amino acids, meaning our bodies cannot produce them and we must obtain them through diet. They are unique among amino acids due to their branched molecular structure and their direct metabolism within muscle tissue, bypassing the liver, which contributes to their historical appeal in sports nutrition.

The allure of BCAAs largely stems from their role in muscle protein synthesis (MPS). Leucine, in particular, is considered the primary driver, acting as a signaling molecule to initiate the cellular machinery responsible for building new muscle proteins. This fundamental role has led to widespread belief that supplementing with BCAAs, especially around exercise, could directly enhance muscle growth and recovery, providing an advantage for athletes striving for peak performance.

The Role of Leucine, Isoleucine, and Valine

- Leucine: Often referred to as the “anabolic trigger,” leucine is paramount due to its direct role in activating the mTOR pathway, a key regulator of muscle protein synthesis. Its presence signals the body to initiate muscle repair and growth processes.

- Isoleucine: While less potent than leucine for MPS, isoleucine plays a significant role in glucose uptake into cells and helps regulate blood sugar levels. This can be particularly beneficial for endurance athletes or during periods of intense training.

- Valine: Valine contributes to muscle metabolism, tissue repair, and the maintenance of nitrogen balance in the body. It also provides energy for muscles and aids in immune system function, though its direct impact on muscle growth is less pronounced than leucine’s.

Initially, early research seemed to support the idea that isolated BCAA supplementation was a critical component for athletes. The logic was simple: if these specific amino acids are key for muscle building, then providing them in concentrated form must be beneficial. This understanding fueled the supplement industry’s focus on BCAAs, making them a staple in many athletes’ regimens.

However, as scientific understanding evolved and more comprehensive studies emerged, a more nuanced picture began to form. This picture challenges the long-held assumptions about the standalone efficacy of BCAAs, especially when compared to whole protein sources.

The high market presence of BCAAs means that many athletes, driven by anecdotal evidence or aggressive marketing, continue to purchase and consume these supplements without fully understanding the current scientific consensus. This narrative aims to provide that evidence-based perspective.

BCAAs and Muscle Protein Synthesis: A Deeper Dive into the Science

The foundational argument for BCAA supplementation rests on their ability to stimulate muscle protein synthesis (MPS). Leucine, as mentioned, is a potent activator of the mTOR pathway, which is crucial for initiating the muscle-building process. This has led many to conclude that supplementing with BCAAs directly translates to greater muscle gains.

However, for muscle protein synthesis to truly occur and result in net muscle gain, all nine essential amino acids (EAAs) must be present in sufficient quantities. BCAAs only provide three of these essential amino acids. While leucine might kickstart the process, it cannot sustain it in the absence of the other EAAs.

The “Building Blocks” Analogy

Think of muscle protein synthesis as building a house. Leucine is like the blueprint, signaling the construction to begin. But you can’t build a house with just a blueprint; you need all the bricks, wood, and other materials (the other essential amino acids) to complete the structure. If you only provide the blueprint (BCAAs), construction starts but quickly stalls because the other materials are missing.

Numerous studies have now demonstrated that while BCAAs can acutely stimulate MPS, this stimulation is often transient and insufficient for sustained muscle growth if the other EAAs are not available. In fact, some research suggests that BCAA supplementation without accompanying EAAs might even lead to a net negative protein balance, as the body might pull other EAAs from existing muscle tissue to complete the protein synthesis process initiated by the BCAAs. This essentially cannibalizes existing muscle, counteracting the very goal of supplementation.

Conversely, consuming a complete protein source, such as whey protein, casein, meat, or eggs, provides all the necessary essential amino acids in the optimal ratios the body needs for efficient and sustained muscle protein synthesis. These complete proteins naturally contain BCAAs, often in higher concentrations than what is found in purified BCAA supplements, ensuring that the “building blocks” are all present when the “blueprint” is activated.

Therefore, for athletes already consuming adequate protein through their diet or through complete protein supplements, adding isolated BCAAs on top of that is unlikely to offer any further physiological benefit in terms of muscle protein synthesis. The body already has all the necessary components. It’s like adding extra blueprints to a construction site that’s already well-stocked with all materials; it doesn’t speed up or improve the building process.

BCAAs for Muscle Soreness and Recovery: Debunking the Claims

Beyond muscle protein synthesis, a common claim for BCAA supplementation is its purported ability to reduce muscle soreness (DOMS – Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness) and accelerate recovery after intense exercise. Athletes often turn to BCAAs hoping to minimize post-workout discomfort and return to training sooner.

The theory behind this claim often revolves around BCAAs reducing muscle damage during exercise or promoting faster repair post-exercise. Some early studies, particularly those that induced severe muscle damage in participants, did show a modest reduction in markers of muscle damage or perceived soreness with BCAA supplementation. However, these were often highly controlled, acute studies that may not translate well to real-world athletic training environments.

When considering comprehensive reviews and meta-analyses, the evidence for BCAAs significantly alleviating DOMS or enhancing recovery for athletes is largely inconsistent or weak, especially when compared to the well-established benefits of adequate overall protein intake.

What the Research Really Shows

One critical aspect largely overlooked is that muscle soreness is a complex phenomenon. It involves micro-tears in muscle fibers, inflammation, and metabolic stress, not just a simple lack of amino acids for repair. While amino acids are necessary for repair, simply providing three of the essential amino acids may not address the multifaceted nature of DOMS.

For individuals already consuming enough protein (typically 1.6-2.2 grams per kilogram of body weight per day), the additional BCAAs do not seem to significantly reduce perceived soreness or enhance objective recovery markers like muscle function or strength restoration. The body is already receiving the necessary building blocks through the diet to facilitate repair processes.

Furthermore, the placebo effect can play a significant role in perceived benefits related to recovery. Athletes who believe a supplement will help them recover faster may genuinely report feeling better, even if the physiological effects are minimal or non-existent. This cognitive benefit, while real for the athlete, does not necessarily mean the supplement is physiologically effective beyond what a balanced diet provides.

In essence, while BCAAs are undoubtedly involved in the muscle recovery process as components of muscle proteins, isolating them and supplementing them in addition to a high-protein diet appears to offer no measurable advantage over consuming complete protein sources when it comes to mitigating soreness or speeding up overall recovery. The current scientific consensus suggests that focusing on overall daily protein intake is a far more effective strategy for recovery than singling out BCAAs.

BCAAs and Performance Enhancement: Fact vs. Fiction

The idea that BCAAs can directly enhance athletic performance is another common marketing claim. This often revolves around perceived benefits such as delaying fatigue during exercise, improving endurance, or boosting strength outputs. The proposed mechanisms include BCAAs competing with tryptophan for uptake into the brain, thereby reducing serotonin production and delaying central fatigue.

While the theoretical basis for delaying central fatigue is intriguing, practical application in human performance studies has yielded inconsistent and generally underwhelming results. The amount of BCAAs needed to significantly alter brain tryptophan levels and thus impact serotonin is often much higher than typically supplemented, and the competitive environment in the body is far more complex.

Lack of Robust Evidence for Direct Performance Benefits

- Endurance Performance: For endurance athletes, some early studies hinted at reduced perceived exertion or slightly improved time to exhaustion. However, meta-analyses typically show no significant improvement in endurance performance with BCAA supplementation in well-fed athletes. The primary fuel sources for endurance activities are carbohydrates and fats, and while BCAAs can be used for energy, their contribution is typically minor compared to these macronutrients.

- Strength & Power: For strength and power athletes, the direct performance benefits are largely absent. Studies examining BCAA supplementation on acute strength output, maximal lifts, or power metrics generally show no significant improvements. The primary determinants of strength and power are training adaptations, proper nutrition (including adequate calories and protein), and recovery processes, rather than isolated amino acid intake.

- Cognitive Performance: Although some theories suggest BCAAs could improve cognitive function during prolonged exercise by reducing central fatigue, empirical evidence directly linking BCAA supplementation to measurable improvements in cognitive performance during real-world athletic scenarios remains weak.

It’s important to differentiate between mitigating some markers related to fatigue and actually improving performance outcomes. Even if BCAAs could marginally reduce certain fatigue signals, this doesn’t consistently translate to faster times, heavier lifts, or better overall athletic output in competitive or training settings.

Many performance-enhancing claims are often extrapolated from in-vitro studies or animal models, or from studies in very specific, highly catabolic conditions (like prolonged fasting or extremely severe calorie restriction) which are not representative of a well-nourished athlete’s typical environment. For the vast majority of US athletes who train regularly and consume a balanced diet with sufficient protein, the direct performance advantages promised by BCAA supplements largely remain unsubstantiated by robust scientific evidence.

The Protein Argument: Why Complete Proteins Outperform Isolated BCAAs

This is perhaps the most critical point in the debate surrounding BCAA supplementation. While BCAAs are undoubtedly essential and play vital roles in muscle metabolism, their isolated consumption frequently pales in comparison to the benefits of consuming complete protein sources. Complete proteins, whether from animal or plant sources, provide all nine essential amino acids (EAAs) that the human body cannot synthesize on its own.

For optimal muscle protein synthesis (MPS) to occur and sustain itself, a full spectrum of essential amino acids is required. As discussed, leucine acts as the “trigger,” but without the other “building blocks” (the other six EAAs), the synthesis process cannot be completed efficiently. Providing only BCAAs is akin to having all the keys to start a car but missing the fuel, tires, and engine—you can initiate something, but you won’t get far.

Sources of Complete Proteins That Contain BCAAs

- Animal Proteins: Meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy products (like whey and casein protein) are excellent sources of complete proteins. They contain all essential amino acids in optimal ratios for human utilization.

- Plant Proteins: While some plant proteins are incomplete, many, particularly when combined intelligently, can provide a complete amino acid profile. Quinoa, soy, and hemp seeds are notable examples of complete plant proteins. Combining legumes with grains (e.g., rice and beans) also provides a full EAA spectrum.

The beauty of consuming complete protein sources is that they naturally provide BCAAs alongside all the other essential and non-essential amino acids your body needs. For example, a typical serving of whey protein isolate (a complete protein) contains a significantly high concentration of BCAAs, often in the ideal leucine-rich ratio, along with all the other EAAs necessary for robust and sustained muscle repair and growth.

Numerous studies have consistently shown that consuming 20-40 grams of a high-quality complete protein (like whey or casein) post-exercise is far more effective at stimulating and sustaining MPS than an equivalent amount of isolated BCAAs. These complete protein sources ensure that once the MPS pathway is triggered by leucine, there are ample supplies of all the other necessary amino acids to complete the protein synthesis process, leading to net muscle gain and efficient recovery.

Therefore, for the vast majority of US athletes, the most effective and cost-efficient strategy for muscle growth, repair, and optimal recovery is to prioritize sufficient daily intake of complete protein from their diet. Supplementation with isolated BCAAs becomes largely redundant if this dietary foundation is met, as the benefits they offer are already encompassed and often magnified by whole protein intake.

When Might BCAAs Be Useful? Niche Scenarios and Considerations

While the overwhelming evidence suggests that for most athletes consuming adequate protein, isolated BCAA supplementation offers no additional benefits, there are very specific, niche scenarios where their use might be considered, though even then, benefits are often marginal or debated.

One such scenario is during prolonged fasted states or extremely calorie-restricted diets, particularly for athletes trying to preserve muscle mass while cutting body fat. In such conditions, where dietary protein intake might be severely limited or irregular, BCAAs could theoretically help to curb muscle protein breakdown and potentially provide a small energy source. However, even in these cases, a small amount of complete protein (like a handful of nuts or a small serving of lean meat) would likely be more effective due to the presence of all essential amino acids.

Another potential, albeit limited, application could be for individuals with severe allergies or dietary restrictions who struggle to consume enough complete protein from whole food sources or traditional protein powders. For instance, someone with a severe milk protein allergy who also cannot tolerate soy or pea protein might consider BCAAs as a way to ensure some essential amino acid intake, though this should be a last resort and ideally guided by a dietitian.

Intermittent fasting protocols, particularly those involving prolonged fasts combined with intense training, might be another area where BCAAs are considered. The idea is that taking BCAAs during the fasting window could help mitigate muscle catabolism without breaking the fast significantly. Again, this benefit is likely marginal compared to consuming complete protein during eating windows, and the primary mechanism for muscle preservation during fasting comes from overall caloric and protein balance across the entire week.

It is important to emphasize that even in these niche situations, the benefits of BCAAs are often debated among sports nutrition experts. The current scientific consensus strongly favors prioritizing total daily protein intake from a variety of high-quality, complete protein sources over the supplementation of isolated BCAAs. For the typical US athlete engaged in regular training and consuming a balanced diet, spending money on BCAAs is likely an inefficient allocation of resources that could be better spent on whole foods or other evidence-backed supplements like creatine or protein powder (if dietary protein targets are not met).

Optimizing Your Protein Intake: Beyond BCAAs

Given the nuanced scientific consensus regarding BCAAs, a far more effective and evidence-based approach for US athletes looking to maximize muscle growth, recovery, and performance is to focus on optimizing their overall protein intake from high-quality sources. This strategy ensures the consistent supply of all essential amino acids, including BCAAs, which are naturally present in complete proteins.

Key Strategies for Protein Optimization

Achieving optimal protein intake isn’t just about quantity; it’s also about quality, timing, and distribution throughout the day.

- Adequate Daily Protein: Aim for 1.6 to 2.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day for most active individuals seeking muscle growth or maintenance. This range ensures sufficient amino acids for muscle repair and synthesis, typically providing ample BCAAs without additional supplementation.

- Diverse Protein Sources: Incorporate a variety of complete protein sources into your diet. This includes lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese, whey/casein), and if preferred, plant-based options like soy, quinoa, lentils, and beans (often best combined to ensure complete amino acid profiles).

- Protein Distribution: Distribute your protein intake throughout the day rather than consuming it all in one or two large meals. Aim for 20-40 grams of protein per meal or snack, roughly every 3-4 hours. This strategy helps to sustain elevated muscle protein synthesis rates throughout the day.

- Post-Workout Protein: While the “anabolic window” is not as narrow as once believed, consuming 20-40 grams of complete protein relatively soon after resistance training (within 1-2 hours) can help initiate the repair and growth process effectively. This could be a protein shake or a whole-food meal.

Prioritizing whole-food protein sources also brings additional benefits that isolated BCAAs cannot provide. Whole foods come packed with micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), fiber, and other beneficial compounds that contribute to overall health, gut health, and athletic performance. These nutritional synergies are crucial for a well-functioning body and effective recovery.

For athletes who struggle to meet their protein targets through whole foods alone due to busy schedules, dietary preferences, or appetite limitations, a complete protein powder (like whey, casein, or a blended plant-based protein) is a highly effective and cost-efficient supplement. These powders provide a full spectrum of amino acids, including BCAAs, in a convenient and easily digestible form, making them a superior choice compared to BCAA-only products.

In summary, for the majority of US athletes, redirecting financial resources from isolated BCAA supplements towards high-quality, complete protein sources (whether from food or comprehensive protein powders) will yield significantly better results for muscle development, recovery, and overall athletic well-being. It’s about building a robust nutritional foundation rather than relying on individual “bricks.”

The Verdict: Are BCAAs Worth Your Money for US Athletes?

After a thorough, evidence-based analysis, the verdict on whether BCAAs are worth your money for US athletes largely leans towards a resounding “no,” with very few exceptions. For the vast majority of individuals who are already consuming an adequate amount of dietary protein from complete sources, supplementing with isolated branched-chain amino acids offers no additional, measurable benefits for muscle protein synthesis, muscle recovery, or athletic performance.

The initial excitement and widespread adoption of BCAAs stemmed from their crucial role in activating muscle protein synthesis, particularly leucine. However, subsequent research has clarified that while BCAAs can initiate this process, it cannot be sustained or optimally concluded without the presence of all nine essential amino acids. Complete protein sources inherently provide these essential amino acids, making isolated BCAA supplementation largely redundant when a solid dietary protein foundation is in place.

Key Takeaways for US Athletes

- Prioritize Complete Protein: Focus your nutritional efforts and finances on ensuring you consume enough high-quality, complete protein daily (1.6-2.2 g/kg body weight). Sources include meat, fish, poultry, eggs, dairy, and well-combined plant proteins.

- Protein Powder as a Tool: If meeting protein targets through whole foods is challenging, a complete protein powder (whey, casein, or plant blends) is a more effective and economical supplement choice than BCAAs, as it provides all necessary amino acids.

- Limited Niche Use: Very specific, extreme scenarios (e.g., prolonged fasting, severe dietary restrictions, or highly catabolic states) might see marginal benefits from BCAAs, but these are exceptions and typically less effective than complete protein.

- Beware of Marketing: The supplement industry is vast, and marketing can be compelling. Always scrutinize claims with an evidence-based lens.

The money spent on BCAA supplements could be far more effectively invested in other areas of an athlete’s regimen. This might include higher quality whole foods, scientifically backed supplements like creatine monohydrate (for strength and power athletes), or even professional guidance from a registered dietitian or certified sports nutritionist to optimize overall dietary strategies.

For US athletes committed to maximizing their performance and recovery, the fundamental truth remains: consistency in training, adequate sleep, and a well-rounded diet rich in complete proteins are the cornerstones of success. While BCAAs play a vital role *within* the context of complete proteins, pouring money into them as a standalone performance enhancer, especially when dietary protein is sufficient, is a practice that current science does not support. Make your supplement choices based on solid evidence, not just hype.

| Key Point | Brief Description |

|---|---|

| 🔬 Science Says No | Isolated BCAAs don’t offer extra benefits for muscle protein synthesis if you consume enough whole protein. |

| 🍖 Complete Proteins Win | Whole food protein (meat, dairy, eggs) provides all 9 EAAs for optimal muscle growth and repair. |

| 💸 Value for Money | Investing in BCAAs is likely a waste. Better to buy quality food or proven supplements like protein powder. |

| 📉 Limited Utility | Only in extreme or severely restricted diets might BCAAs offer marginal, limited benefits. |

Frequently Asked Questions About BCAAs and Athletes

▼

While BCAAs, particularly leucine, initiate muscle protein synthesis (MPS), they do not provide all essential amino acids needed for sustained muscle growth. For most athletes consuming enough protein from whole food sources, isolated BCAAs offer no added benefit over complete proteins for muscle building.

▼

The evidence for BCAAs significantly reducing muscle soreness (DOMS) or speeding up recovery for well-nourished athletes is weak and inconsistent. Adequate intake of complete proteins from diet is a far more effective strategy to support post-exercise repair and recovery.

▼

For optimal muscle protein synthesis and recovery, complete protein powder (like whey, casein, or a full-spectrum plant blend) is significantly better than isolated BCAAs. Protein powder provides all essential amino acids required to fully build and repair muscle tissue, whereas BCAAs only provide three.

▼

Despite some theories, robust scientific evidence does not consistently support BCAAs significantly enhancing athletic performance, strength, endurance, or effectively delaying fatigue in well-fed athletes. Performance gains are primarily driven by training, proper nutrition, and overall recovery.

▼

BCAA supplementation might offer marginal benefits in very specific, niche scenarios, such as during extreme fasting, severe calorie restriction, or for individuals with very limited complete protein intake due to allergies. However, for most athletes, these benefits are negligible compared to sufficient whole protein intake.

Conclusion

For US athletes navigating the complex world of sports nutrition, the evidence strongly suggests that focusing on branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) supplementation as a standalone strategy for performance or muscle growth is largely an inefficient use of resources. While BCAAs play an undeniable role in muscle physiology, their benefits are most fully realized when consumed as part of a complete protein source. Prioritizing adequate daily intake of protein from whole foods—or a comprehensive protein powder when dietary needs aren’t met—remains the gold standard for supporting muscle protein synthesis, enhancing recovery, and optimizing athletic performance. Investing in a well-balanced diet and foundational supplements proven by robust science will yield far greater returns than relying on isolated BCAAs.